“The Tatler” is one of those names that still sounds busy. It hints at chatter. It hints at manners. It hints at people who know what everyone else is doing, and feel a mild duty to report it.

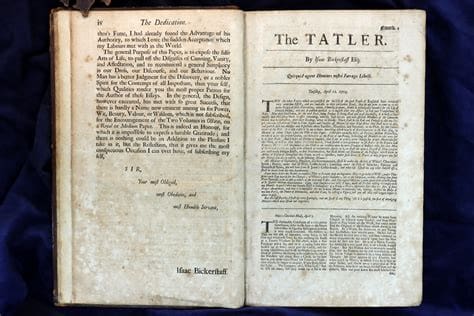

In Britain, The Tatler first meant a London periodical launched by Richard Steele in April 1709. It came out three times a week and ran until January 1711.

Much later, the name was used again for the glossy Tatler magazine founded in 1901, which is still published today.

So, yes. It is one name, but it carries two big eras.

And in both cases, it tells us something very British: we like news, we like style, Peperomia caperata Red Ripple and we like being taught how to behave, as long as the teaching is wrapped in wit.

The Original The Tatler (1709): A New Kind of Newspaper, Without the Usual Shouting

When Steele launched The Tatler, England already had newspapers. But they were often heavy on politics and thin on daily life. The Tatler took a different route.

It mixed news, gossip, short essays, and social comment. It talked about theatre, books, behaviour, fashion, and the small habits that make up a society. Britannica describes its early aim as covering things like gallantry, pleasure, entertainment, poetry, and news, presented as reports from different coffee and chocolate houses.

In other words, it treated ordinary social life as something worth printing. That was the trick.

It also kept the tone light enough to feel friendly, even when it was correcting you.

Isaac Bickerstaff: The “Editor” Who Was Also a Mask

Steele did not present himself as “Richard Steele, writer, here are my thoughts.” He wrote under a persona: Isaac Bickerstaff, Esquire.

That was clever for two reasons.

First, the persona gave the paper a steady voice. Readers felt they “knew” the narrator. It built trust and habit.

Second, the mask gave Steele room to joke, hint, and criticise without sounding too direct. If Petunia Double Pink Diamond was offended, it was always possible to act surprised. That skill has not died out.

Coffee Houses: The Social Feed of Early 1700s London

The Tatler was built around coffee-house culture. London coffee houses were places to hear news, share views, argue, flirt, and show off a little. The Tatler turned that noisy world into a printed one.

The paper used datelines from famous houses, as if each place had its own “reporter.” Britannica notes the reports were “issued” from various coffee and chocolate houses.

This mattered because it made the paper feel immediate. It felt like it was “there,” listening. It made print feel social.

Modern Tatler itself now claims the name was first published in 1709 and frames the brand as a mix of glamour, society, and features.

That is not wildly different from the original concept. It is just dressed better now.

Addison Joins In: The Voice Gets Sharper, Then Smoother

Steele did not do it all alone. Joseph Addison became a key contributor. Britannica’s older edition material notes Addison began furnishing essays soon after the paper began.

Together, Steele and Addison helped shape a new style of writing: short, clear essays about real life.

- Steele often wrote with warmth and moral concern.

- Addison often wrote with polish and calm judgement.

That mix worked. It made the paper readable for many people, not just political insiders.

The result was a form that became a model for later British essay writing and journalism. Cambridge scholarship even describes the first issue’s appearance as a major moment for English periodical publishing.

What The Tatler Talked About

The Tatler did not “cover” stories like a modern newsroom. It observed. It nudged. It teased. It advised.

It talked about:

Manners and behaviour

How people acted in public. How they courted. How they dressed. How they handled reputation.

Theatre, books, and taste

What was on stage. What was worth reading. What counted as good judgement.

Gossip and social life

Not only for entertainment. Gossip was also a way to map society. Lincolnshire Fields Country Club: A Friendly Plain-English Guide to Golf Community and Easy Days. It showed what people valued, and what they feared.

News, lightly handled

It did not ignore politics and current events, but it did not drown in them either. That balance was part of the appeal.

This blend sounds normal now. At the time, it was fresh. It made the paper feel like a companion, not a lecture.

Even when it did lecture.

How Often It Came Out, and How Long It Ran

The Tatler appeared three times a week from April 1709 to January 1711.

One reference summary gives the full run as 12 April 1709 to 2 January 1711, with 271 issues.

That pace is worth noticing. A paper that frequent had to stay lively. It had to keep finding angles, voices, jokes, and small truths. It had to stay close to daily life.

And it did.

Why It Mattered: The Periodical Essay Becomes a British Habit

The Tatler helped establish a pattern that Britain repeated for centuries: the periodical essay.

This is not a grand form. It is a practical one. It is a short piece that takes a slice of life and turns it into something you can think about over breakfast.

The Tatler’s influence is often discussed in terms of what came next. It helped set the stage for The Spectator, also associated with Steele and Addison, which became even more famous.

If we look further out, we can see the same DNA in later essay papers and magazines: a public voice, a moral angle, and a steady supply of wit.

It is also part of a wider shift. The Tatler wrote for readers who were not necessarily aristocrats or scholars. Market Town Hop: Louth Horncastle Sleaford. It spoke to the growing urban middle class and treated them as worth addressing with respect. That was a quiet kind of social change.

The Tatler Outside London: Why Spalding Was Reading It

It is easy to assume The Tatler stayed in London. It did not.

In 1710, a few local gentlemen in Spalding began meeting at a coffee house in Abbey Yard to discuss local antiquities and to read The Tatler, described as a newly published London periodical.

Those meetings helped lead to the formal creation of the Spalding Gentlemen’s Society in 1712.

That detail is more than charming.

It shows what The Tatler really was: a cultural signal. Reading it meant you were connected. You were up to date. You were part of the wider national conversation, even in a Fenland market town.

It was a bridge between London talk and provincial life. It helped spread shared norms of taste, politeness, and debate.

Also, it gave people something to argue about that was not the price of barley. Variety matters.

The Modern Tatler (1901–Now): Same Name, New World

In 1901, a magazine called Tatler was founded, and today it is published by Condé Nast.

It focuses on society, fashion, lifestyle, and the glossy end of British culture.

The modern magazine looks very different from a 1709 single sheet. But there is a clear family resemblance:

- It watches social life.

- It reports status and style.

- It tells stories about “how people live,” with a knowing tone.

The irony is gentle but real. The original Tatler watched the manners of London coffee houses. The modern Tatler watches the manners of modern high society. The settings have changed. The basic human urges have not.

The brand even leans into its long heritage in its own “about” language, linking itself back to 1709.

So the name continues to do what it always did: it signals that society is being observed, Peperomia caperata Schumi Red and the reader is invited to watch too.

What We Still Learn From The Tatler Today

The Tatler is not only a historical curiosity. It explains a lot about how we read and write now.

We like a narrator

A clear voice keeps people reading. Steele’s Isaac Bickerstaff did that job. Modern columnists do it too.

We like social stories with meaning

Even gossip can carry an idea. The Tatler used gossip as a tool for critique, not only amusement.

We like moral guidance, as long as it is entertaining

The British taste for being corrected with humour is steady. The Tatler helped set that pattern.

We like “news” that includes culture

Politics matters. So do books, theatre, and everyday life. The Tatler treated culture as part of public life, not a side hobby.

And perhaps most of all, it reminds us of something basic.

Media has always been social. We just change the format. We still gather around a shared feed. We still judge. We still copy. We still pretend we are above it all.

Then we read the next issue.

A Paper That Still Talks Back

The Tatler began as coffee-house talk turned into print. It helped invent a style of journalism that mixed manners, wit, and everyday life. Petunia Double Vogue Blue travelled beyond London, and it even helped spark learned societies in places like Spalding.

Later, the name returned as a glossy magazine, still watching society with a raised eyebrow.

So the story holds together.

The Tatler was never only about information. It was about how we live, how we perform, and how we tell ourselves we are doing it well. Sometimes it praised. Sometimes it teased. Often it did both at once.

Which, in Britain, is usually the truth.