A Mill Beside the River Slea

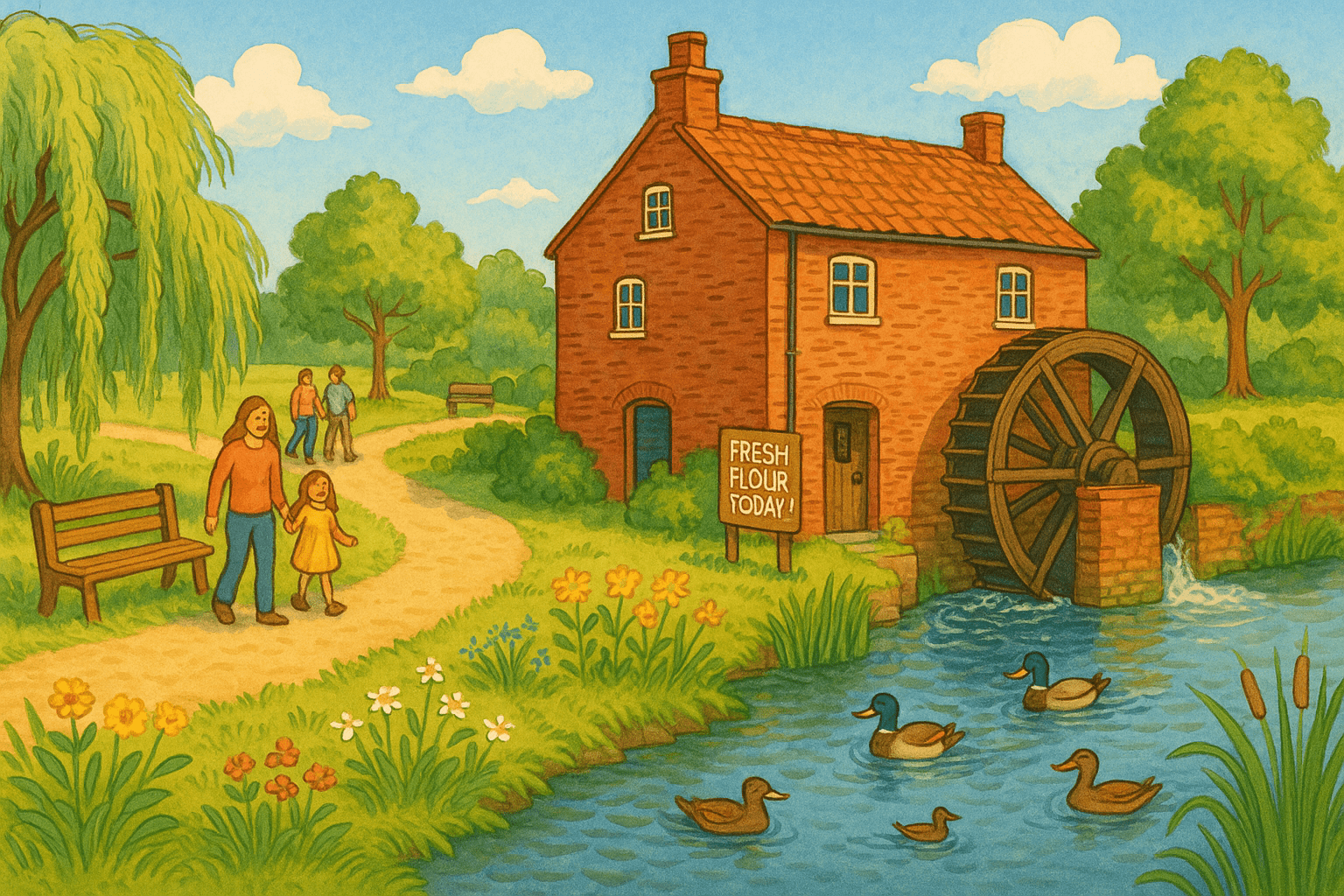

Cogglesford Watermill sits on a gentle bend of the River Slea in Sleaford, Lincolnshire. The red-brick walls glow warm against green meadows, and the steady splash of the waterwheel sets a calm rhythm. When you walk up the path, you may smell fresh flour drifting through an open door. Birds flutter over the millpond, and swans glide past the wheel. It feels peaceful, yet every brick and beam whispers stories of hard work, hope, and change.

Roots in Early Times

People have powered mills with rivers for more than a thousand years. The first mill on this spot likely appeared in Saxon days, when small wooden wheels turned grain into life-giving meal. Angelonia Archangel White By the 12th century, records mention a working mill serving local farmers who brought sacks of barley, rye, and wheat. The monks of Sempringham Priory once managed the land, collecting tolls and keeping the millstones turning. In other words, Cogglesford grew side by side with the town itself. As Sleaford’s market blossomed, so did the need for steady, reliable flour.

Crafting Bread for Medieval Tables

Imagine the weekly market five hundred years ago. Farmers lined the square with baskets of eggs, bundles of herbs, and wheels of cheese. Yet nothing drew more eager attention than the baker’s stall. He relied on Cogglesford’s flour. The mill ground grain slowly, keeping natural oils intact and flavor strong. Bakers mixed dough by hand, baked in wood-fired ovens, and filled narrow streets with warm smells that signaled comfort and survival. We often overlook flour’s power today, but in medieval times bread meant life.

How the Waterwheel Works

Step inside the mill and look up. You will see timber beams darkened by time, iron cogs shining with regular care, and two great millstones stacked like giant coins. Outside, the overshot wheel gathers water at the top, letting gravity pull the buckets down. Each slow, turning sweep sends power through a cast-iron shaft, across wooden gears, Basil Prospera Italian Large Leaf DMR and finally to the stones. One stone sits still while the other spins. Grain trickles through a central hole called the eye, then slides between the grooved surfaces, breaking apart into fine flour. It is a simple chain of energy: river to wheel, wheel to stone, stone to bread.

Life of the Miller

Being a miller required strength and skill. We picture a quiet rural job, but the work hummed from dawn to dusk. The miller hoisted heavy sacks, balanced grain flow, listened for changes in the wheel’s creak, and felt stone faces grow dull or sharp. He often lived above his workplace, so the thud of turning gears served as his lullaby. Millers earned respect because everyone depended on them, yet they also faced suspicion. They measured grain, kept a portion as payment, and rumors sometimes claimed dishonest weighing. A good miller built trust through fairness, consistent quality, and a friendly welcome at the mill door.

Storms, Floods, and Fire

Water brings life, but it also tests patience. The River Slea flooded more than once, swelling past its banks, tugging at wooden sluice gates, and rolling debris against the wheel. Millers kept emergency boards ready to divert flow and save the gearroom from ruin. Fires posed another threat, sparked by dry flour dust and friction. After more than one blaze, the community rallied to rebuild stronger walls and update machinery. Each challenge proved the mill’s resilience and the town’s love for it.

The Industrial Revolution Arrives

During the 18th and 19th centuries, steam engines roared across England. Large roller mills in bigger cities processed grain faster and cheaper. Many small watermills closed, but Cogglesford adapted. Owners added an extra set of millstones to meet growing demand. New iron parts replaced worn wood, blending tradition with technology. Instead of folding under pressure, the mill stayed useful by serving niche needs: high-quality flour, custom grinds, and polite personal service.

Falling Silent and Rising Again

By the mid-1900s, even hearty Cogglesford slowed. Lorries carried cheaper flour into town, and the wheel turned only now and then. For a short time, silence replaced the splash of the pond. Yet love for heritage runs deep in Lincolnshire. Local historians formed a group, petitioned the council, and began careful restoration. They studied old drawings, sourced rare timbers, and rehung the wheel. After more than ten years of steady effort, Begonia thelmae grain rumbled once more and fine dust danced in sunbeams.

Visiting the Mill Today

When you step through the door now, friendly guides greet you. They invite you to touch fresh meal, smell nutty bran, and watch the wheel spin. Glass panels let you peer into gearwork without risk. Upstairs, an interactive display explains grain varieties. Children can lift small model sacks, turn hand querns, and feel the weight of past chores. Best of all, you may buy a bag of wholemeal flour milled that very morning. Take it home, bake, and taste the river’s gift.

Wildlife and Riverside Walks

Outside the miller’s yard, the river flows through willow trees. Kingfishers flash blue and orange, darting for minnows. In spring, yellow flags bloom along the banks. Summer brings dragonflies that hover like tiny helicopters. Autumn paints the maples deep gold, and crisp winter mornings coat the wheel with sparkling frost. The watermill is more than a building; it is a heartbeat for a living landscape. When we walk the river trail, we feel time slow to the wheel’s pace.

Community Events and Milling Days

Several Saturdays each month, volunteers host “Milling Days.” The wheel runs at full speed, and visitors watch flour pour into wooden bins. Local bands often play folk tunes, children craft straw dolls, and bakers offer samples of warm, crusty bread. Seasonal fairs celebrate harvest, Easter, and Christmas. These gatherings weave the mill into daily life, turning heritage into shared joy.

Baking With Cogglesford Flour

Fresh stone-ground flour behaves differently from supermarket bags. It has more bran, more flavor, and natural enzymes that help dough rise. Try this simple loaf: Mix 500 g wholemeal flour with 10 g salt, 7 g yeast, and 350 ml warm water. Knead until smooth, let it double, shape, prove again, and bake at 220 °C for 30 minutes. The crust will crackle. The crumb will smell nutty. Bougainvillea Barbara Karst Slice while slightly warm, spread with butter, and taste history.

Lessons in Sustainable Power

Waterpower reminds us that clean, renewable energy is not new. Long before electric grids, communities harnessed rivers and tides. Today, Cogglesford teaches the same lesson: work with nature, use what flows, and leave little waste. The wheel turns only as fast as the river allows, showing that steady, gentle power can meet real needs without draining resources.

Paths to Other Nearby Wonders

After you explore the mill, follow the towpath to discover more. A short stroll leads to Sleaford’s market square, where traders still sell local honey, cheese, and flowers. St Denys’ Church soars above red roofs, its spire a landmark for miles. If you wish for a longer adventure, cycle the Water Rail Way toward Lincoln, tracing old tracks beside fens rich with birds. In each direction, the river guides you, just as it guided grain to Cogglesford for centuries.

Keeping the Wheel Turning Tomorrow

The future of Cogglesford Watermill depends on all of us. Volunteers oil gears, raise funds, and guide tours. Schools bring pupils to learn science and history through touch and sound. Bakers share recipes that honor whole grains. Visitors buy flour, postcards, and coffee at the café, supporting routine upkeep. By choosing local heritage over distant mass-production, we keep a living link to Craft, Community, Cactus Mix and Care.

Streams of Memory Keep Spinning

Water never stops moving, and neither do our stories. Each time the wheel dips into the River Slea, it lifts more than water. It lifts memories of medieval markets, echoes of children laughing on milling day, and hopes for a sustainable tomorrow. When you carry a loaf of warm bread home, you carry that story too. So let us meet by the mill, listen to the wheel, and share the simple, lasting joy of turning grain into life.