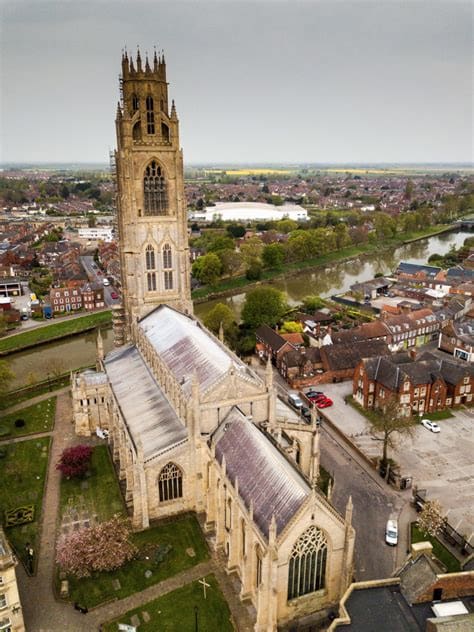

St Botolph’s Church sits on the river in Boston, Lincolnshire, and does not really bother with modesty. The tower climbs to about 266 feet, one of the tallest medieval parish church towers in England, and it rises from flat fenland so that it looks even taller again.

Locals call it the Boston Stump. The nickname is blunt and affectionate. It tends to swallow the formal name so completely that people talk about “going up the Stump” rather than “visiting St Botolph’s”. You and I see the same thing either way: a huge late-medieval church, Pansy Cool Wave Blue a landmark for ships in The Wash, and a building whose story runs from Anglo-Saxon saints to New England Puritans to flood defences and Lego bricks.

A parish church that thinks like a cathedral

We stand in the Market Place or by the quay and the scale becomes clear. The church stretches to almost a hundred yards in length, with a big Perpendicular nave and clerestory, broad aisles and a long chancel, all in pale ashlar stone. The tower then stacks another great block of masonry on the west end and finishes with an open octagonal lantern.

On paper, this is a parish church. In practice, it behaves rather like a small cathedral that somehow missed out on the extra title. It dominates the town plan, it anchors the skyline for miles, and it sets the tone for the riverside. When we move around Boston, we keep finding that the Stump has quietly wandered back into view.

Inside, the scale continues. Tall clustered piers, high windows and long sightlines pull our eyes along the nave towards the chancel. The building feels airy rather than heavy, which is impressive when you remember how much stone is sitting above your head.

From Botolph’s town to Boston Stump

The church dedication reaches back to St Botolph, a seventh-century missionary who preached in this part of eastern England. Later tradition links him with a monastery at Iken in Suffolk and with work among local communities along the coast and the fens. The town name “Boston” is widely thought to come from a version of “Botolph’s town” or “Botolph’s stone”.

The present building is much later. Work on the current church started in 1309, as usual beginning with the chancel at the east end. The nave and aisles followed and were completed around 1390. Engineers then ran into trouble. The soft ground close to the river caused foundation issues, so the chancel was extended to help prop up the structure and to keep the great arcades from leaning too far. That fix has held remarkably well. To this day the tower leans by less than half a centimetre despite its height and its proximity to the water.

The tower itself was not begun until about 1450. Builders dug deep into the wet ground, created broad foundations and then took roughly seventy years to raise the Stump to its finished height between 1510 and 1520. Parsley Pesto Recipe: A Delicious and Nutritious Way to Use Fresh Parsley. The result is a classic piece of late Perpendicular design, with strong vertical lines and an elaborate lantern that gives the whole structure a sense of lightness it probably does not feel.

A tower that works for a living

The Stump looks decorative, but it always had practical work to do. From the sixteenth century onwards, the tower acted as a navigation mark for sailors in The Wash and on the fenland rivers. Boston’s fishermen and merchants used it as a daymark, and on a clear day you can see it from the Norfolk side of the bay.

There is long-standing local talk that the lantern once held lights at night to help seafarers. Evidence sits somewhere between documented detail and half-remembered habit, but rings and fittings in the tower suggest that lamps could be hung there when needed. Either way, the building earned its keep as a stone lighthouse as well as a place of worship.

In the twentieth century the tower took on another navigational role. During the Second World War, Lincolnshire became “Bomber County”, and aircrews used the Stump as a landmark when flying over the flat land below. Stone that once guided medieval traders was quietly helping to bring home modern aircraft.

The bells add one more layer. Today there are 26 bells in total, including a ring of ten hung for change-ringing and a carillon of fifteen. The sound carries well across the town and out over the river, which feels entirely fair for a tower that size.

Puritans, Pilgrims and a path to New England

St Botolph’s sits at the centre of one of the more tangled links between England and New England. In 1612, the Reverend John Cotton became vicar here. He was a leading Puritan voice, keen to “purify” the Church of England from within. His preaching style was austere. Services under his care ran long on sermons and short on music. The prominent pulpit in the nave, installed in his time, is still known as Cotton’s Pulpit.

Pressure on Puritan clergy grew under Archbishop Laud, and by the 1630s Cotton faced real trouble for his views. In 1633 he left Boston for the Massachusetts Bay Colony. There he helped shape the young community of Boston, Massachusetts, carrying both his theology and the town’s name across the Atlantic.

The story does not stand alone. Earlier separatists with links to this part of Lincolnshire tried and failed to escape via the nearby creeks and The Haven. Later migrants carried Boston connections into wider colonial networks. Today, plaques, the Puritan Pathway and the Cotton Chapel inside the church mark those ties. Memorial stones remember figures such as John Winthrop and Anne Hutchinson, and partnerships between the two Bostons keep the relationship politely alive.

When we walk round the church or sit under the arcade, we stand in a parish that has been arguing with itself, Pelargonium x fragrans Nutmeg-Scented Geranium and with the wider church, for centuries. The stones are steady. The ideas have been far less so.

Floods, restorations and stubborn stone

Like many large medieval churches, St Botolph’s has taken a fair amount of damage over time. During the English Civil War, accounts describe Parliamentarian soldiers using the building as a convenient shelter for horses and even firing muskets at the walls for sport. The fabric survived, but the message about military manners was not ideal.

The nineteenth century brought the usual round of Victorian concern. Architects such as Sir George Gilbert Scott worked on the church in the 1840s, followed by George Place of Nottingham in the 1850s and later Sir Charles Nicholson in the 1920s. They repaired stonework, renewed fittings and added a rich reredos that looks older than it is.

In December 2013, a tidal surge pushed water from the North Sea up into The Wash and along the Haven. Parts of Boston flooded, including the area around the church. The Boston Stump Restoration Trust played a key part in recovery and in raising funds for further conservation work, including projects supported by national heritage bodies.

The result of all this effort is a building that still reads as authentically medieval while quietly carrying a surprising amount of twentieth and twenty-first century engineering, grouting and fundraising under the surface. We get to admire big traceried windows and tall arcades without worrying too much about what keeps everything in place, which is probably how most of us prefer it.

Inside the Stump: light, glass and quiet corners

Walk through the main doors and the first impression is height and light. Tall windows flood the nave with daylight. Stone arcades march down each side, and the open space feels almost civic in its scale. You and I can move quite freely, which suits a church used to handling both worshippers and visitors. Lincoln England: A City Where History Breathes Beside Modern Life.

Several features repay slower attention:

- The font near the west end, used for local baptisms over many generations.

- The reredos at the east end of the chancel, completed in 1914 yet blending so well that many people assume it is medieval.

- The Cotton Chapel, with its links to Puritan history and New England connections.

- The library, founded in the 1630s and developed over time, which once served as a serious working collection for local clergy.

Stained glass here is a mix of fragments and later work. The original medieval glass did not survive intact, for reasons that rarely need much imagination. Later windows bring in Victorian colour and narrative, giving the interior a layered feel that mirrors the town’s own history.

Music also has a strong presence. The church supports choirs, concerts and a programme of events alongside regular services. The organ and the acoustic together make the building attractive for recitals, and the tower bells add their own contribution from above.

Visiting today: tower steps, café stops and Lego bricks

For a building of this size and age, St Botolph’s feels surprisingly approachable. The church is generally open from morning to late afternoon most days, with Sunday hours adjusted around services. Entry to the main space is free, though donations clearly help keep the lights on and the stonework stable.

Several features make a visit more than a quick look round.

Tower Experience

You and I can climb the tower on organised Tower Experience visits. The climb involves about 209 steps in a tight spiral, with pauses at different stages. At the top, views stretch across Boston, the surrounding fens and, on a clear day, out towards The Wash and sometimes Norfolk. Digital displays inside the church help you match what you see to local landmarks if heights are not your favourite thing.

Refectory and gift shop

At ground level, the Refectory café and the gift shop provide the usual mix of drinks, light lunches and souvenirs. It is possible to treat the whole visit as a simple town-centre coffee stop with very dramatic architecture attached, which is not a bad way to slip heritage into an ordinary day.

Lego build and family activities

One more detail says a lot about how the parish approaches visitors. The ongoing St Botolph’s Big Lego Build project aims to create a large Lego model of the church, roughly two metres high, funded brick by brick through sponsorship. Families can sponsor a piece, watch the model grow and talk about the real building at the same time.

Younger visitors also find maze walks, digital screens that offer virtual “bird’s-eye” views of Boston, and trails that guide them through the space. Lincolnshire Animal Hospital: Caring for Pets Supporting People. This is a church that expects children, cameras and a fair number of slightly lost tourists, and it handles all three with calm good manners.

Shared stone, shared story

St Botolph’s Church stands on the riverbank as it has for centuries, looking across the docks, the Market Place and out towards the drained fields. The building began as a statement of local wealth and piety in a medieval trading port. Over time it picked up other jobs: daymark for sailors, landmark for bomber crews, stage for Puritan sermons, flood victim, community hub, tourist stop and, more recently, Lego template.

When we step through the doors, we add one more layer to that story. We join traders, pilgrims, parishioners, airmen, volunteers, restoration architects, school parties and quiet weekday visitors, all sharing the same stone floor at different points in time. The Stump keeps watch above us, steady as ever, and the town continues to move around its feet.